The Holy Family – Rembrandt

Reposted from: Costing Not Less Than Everything

I posted this painting in another post and wanted to write more about what I thought and felt about it.

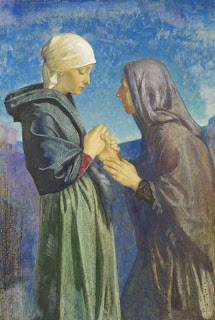

This is a domestic scene, first and foremost – quotidian and earthbound. The dwelling is dark, probably cold, draughty and damp. Rembrandt painted several similar pictures of the Holy Family, in which the relative meanness of the surroundings contrasts with domestic warmth and love. Saint Joseph is, as is often the case, back in the shadows, an older, shaded, quieter figure. The Madonna and Child are always foregrounded. That was the convention of the times – but he is not redundant. Joseph is working at his trade (and there is rather a nice rendition of a drill hanging on the wall). Whatever the artistic convention, Venerable Fulton Sheen contends that the common conception of Joseph as an older, less powerful man than the conventional young Jewish husband of the day is incorrect. He describes Joseph as young, virile, consecrated to God and to his family.

What is striking about the painting is the stance of the Madonna. The Baby is at reast – and she takes a moment from her reading to bend forward and check the sleeping Child. Her expression is confident, loving, slightly watchful. She has one foot comfortably on a footstool, stretched out towards the small warming fire. The Child is in a rather marvellous wicker cradle, lovingly painted – the kind of cradle one can rock with one’s foot while otherwise engaged, or resting. The cradle has a hood to keep out draughts and other dangers – and a cloth is draped across the top to protect further. I saw the same arrangement recently when a mother brought her child into a Council office to register the birth – a small blanket over a car seat, whipped back to reveal a tiny babe. The Child sleeps peacefully, with one hand out of the heavy warm covers – which one critic likens to the blood of the Passion, prefigured here in the red blanket and in Mary’s red dress. The same writer states that Mary’s book is the Old Testament, foretelling the birth of the Child she now looks at, uncovering him to the world.

The Madonna here is no Queen of Heaven. She is almost plain – buxom, humbly and ‘respectably’ dressed. The light (from where?) catches her face, her book, the head of the sleeping Child and the angels tumbling around the crib. And behind, Joseph carries on with his patient work. The work folds together the domestic, human and ordinary with the divine and eternal, represented in the ordinary symbols of family life and suffused with the supernatural.

One site I have looked at describes Rembrandt as “sans doute le plus grand peintre de l’âme humaine” – “without doubt, the greatest painter of the human spirit.” Another writer suggests that the model for Our Lady is Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s housekeeper and common-law wife – and that the Child is posed by Rembrandt’s son Titus by his late wife, his beloved Saskia. Titus was the only child of the four that Saskia bore who survived. Rembrandt’s biographers stress his sorrow and disappointment, both in his material dealings and in his domestic life. None of us are going to know for certain the truth of the artist’s life – but his paintings speak, to me at least, of the warmth and safety of a small family in perilous times, lit by divine light and guarded by angels.

It is a lovely painting - I love the way Joseph is quietly working away in the background.

ReplyDelete